AFRICAN SLEEPING SICKNESS

Human and animal trypanosomiasis are exemplary for the One Health concept

A CENTURY OF FAILS.

120 years ago, African sleeping sickness was not an NTD, a neglected tropical disease of poverty.

For decades it was considered the major scourge of Africa, with more than three dozen sub-Saharan countries suffering from human trypanosomiasis. Colonial troops were obviously also affected, and hence an arms race to combat sleeping sickness was launched in the early 20th century. Many European countries were involved, in particular the British Empire. Robert Koch was sent by William II, the German Emperor. By 1906, he erroneously reported that he had cured sleeping sickness. However, his 450-page report to the ‘Kaiserliche Gesundheitsamt’, submitted in 1909, is still a prime example of scientific accuracy - but also an encyclopaedia of horror. Both German and British troops built concentration camps to facilitate studies on sleeping sickness. The patients were considered dangerous and thus, were often bound. The inhumanities in East Africa were easily surpassed in the Congo Free State, a private property of Leopold II of Belgium.

With the end of colonialism the interest of the Western world in Africa vanished - until today.

THE DISEASES.

African trypanosomes cause more than one disease. Human sleeping sickness comes in two basic forms that are caused by two trypanosome (sub)species, Trypanosome brucei gambiense and Trypanosome brucei rhodesiense. Early symptoms are flu-like with fevers, headaches, joint and muscle pain, accompanied by a characteristic inflammation of the lymph nodes. Depending on the infective agent the disease can proceed to the second phase within weeks or after 1-2 years. The parasites pass the blood-brain barrier, which is accompanied by the onset of the eponymous sleep disorder and severe neurological symptoms, including apathy and mental dullness, spasms and paralysis, followed by coma. Untreated patients die. Diagnosis is difficult and has to be conducted early. In the early 21st century, very effective control programmes in many African countries have resulted in a decline in sleeping sickness cases; however, this is dependent on intact infrastructure. Today, sleeping sickness is re-emerging in the poorest and most unstable African countries, such as South Sudan.

NAGANA. Sleeping sickness is just one facet of trypanosome infections. Probably the most negative impact that trypanosomes have in Africa is a socio-economic one. Trypanosomes cause devastating animal plagues, of which Nagana is the most prominent one. The total losses, in terms of agricultural gross domestic product, are estimated at € 4.2 billion per year.

Since 2009, we have established a tight collaboration with scientists in Nairobi.

RESEARCH IN NAIROBI AND WÜRZBURG.

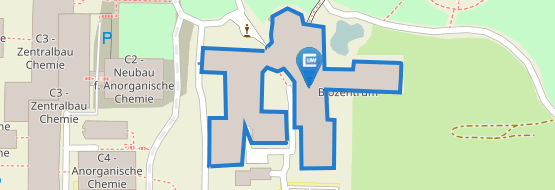

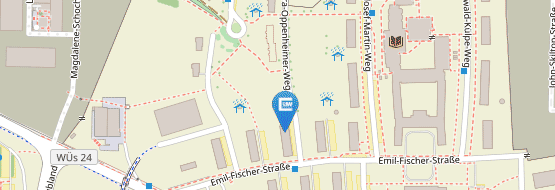

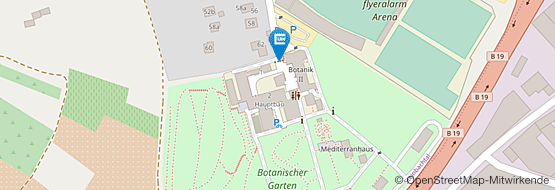

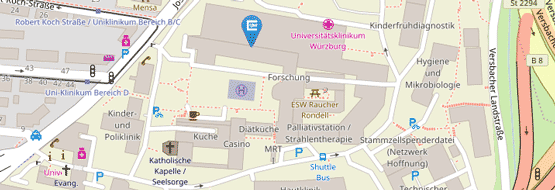

In 2009, we have established a tight collaboration with scientists in Nairobi. The core team consists of Francis McOdimba, Daniel Masiga (Nairobi), and Markus Engstler (Würzburg).

We have shown that survival of the parasite in the host is aided by flagellar motility and rapid endocytosis. Both processes combine to remove host antibodies from the trypanosome cell surface. We have succeeded in detailing - on the single cell level and with millisecond accuracy - the mode of trypanosome swimming in vitro, and in the diverse and crowded environments of the host. We show that different trypanosome species have adapted to distinct infection niches, such as the circulation or tissue spaces. They have evolved a special cellular waveform that allows perfect adaptation to discrete biological niches. Trypanosoma congolense is an exception as it is a bad swimmer. This species has evolved a different survival strategy.

Our future research will include population genetics and ecology, to consider the amazing evolutionary success of trypanosomes, which can effectively populate any vertebrate. All our work was generously funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) und the framework of a unique funding scheme, the German African Cooperation projects in Infectology.

In 1916, the pharmaceutical company Bayer developed Suramin, which was marketed as Germanin. It is still being produced and used today.

Germanin only helps against the first stage of trypanosomiasis and it is highly toxic. Nazi Germany declared the invention of Germanin as a great colonial feat, and it was featured in books and even appeared in horrible propaganda movies. With the end of colonialism the interest of the Western world in Africa vanished - until today. Sleeping sickness continued to be a major health problem, but no investment into diagnosis or drug development was done until the end of the century. In the 1980s, the trypanocidal potential of the cancer drug eflornithine was discovered. It was soon considered the resurrection drug, as it was also effective against second phase sleeping sickness. However, eflornithine was subsequently withdrawn from the market as it was not profitable as a cancer drug. An international campaign led by the United Nations and several NGOs, in particular the Nobel prize-winning Doctors Without Borders, finally forced the industry to donate the remaining supplies of eflornithine. In 2001, it was found that eflornithine also effectively eliminates facial hair in women. Only with the introduction of Vaniqa, which contains 13.9% eflornithine, was the production of the most important anti-sleeping sickness drug ensured. What an ironic twist.